One Chimp’s Journey to Sanctuary – part two

#KareemStrong

If you missed part one, start here

Lisa Jones-Engel was Kareem’s caregiver at New York University’s Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates (LEMSIP) from the time he was only 3 weeks old.

Lisa, now a professor at the University of Washington focusing on the human-primate interface and the ethics of using primates in research, shared the details of Kareem’s early life with me in an hour-long phone interview.

Kareem’s story starts with the heart-wrenching fact that, like many chimpanzees who were born in research facilities, he was pulled from his mother at just a few days old. It’s difficult to think about the devastation that Kareem’s mother must have endured when her baby was pulled from her loving arms. Caregivers swaddled him in diapers and placed him in the lab’s chimpanzee nursery. There were many other baby chimps waiting to meet him. Labs throughout America had stepped up chimpanzee breeding for a variety of research and testing, which supposedly were going to help scientists cure diseases. Years later, the U.S. would be the last country in the world to end medical testing on chimpanzees.

Kareem, today, at Project Chimps. Photo by Crystal Alba

Kareem goes home on weekends

Lisa became a weekend nanny for Kareem and his two infant group mates, Digger and Regis.

On the weekends, she would take the three infant chimps, place them on the passenger seat of her red Dodge Omni, and drive them to her nearby apartment in Sterling Forest. She entertained them, socialized them, bonded with them, and loved them. On Mondays, they went back to the nursery in the lab.

Lisa worked with Dr. James Mahoney, who ran LEMSIP and was a firm believer in the need to subject chimpanzees to biomedical research. But Mahoney himself did not believe we had a right to engage in research, only a need. And late in his career, he had a change of mind and became known for his effort to move more than 200 chimps and monkeys to sanctuaries ahead of their scheduled transfers from LEMSIP to other labs. After his change of heart, Dr. Mahoney believed the best thing his team could do was to make sure the chimps were as solid and secure as they could be, psychologically, knowing they were bound for research. To this end, he assigned Lisa the task of being surrogate mother and role model to the young chimps.

Lisa repeated her weekend caregiving routine until the chimps were 1 year old, when they moved into the lab’s nursery full time. Lisa began to work with other infant chimps but visited Kareem and his group mates in the nursery as often as she could.

Nancy takes over Kareem’s care

Nancy Megna joined Lisa at LEMSIP in 1991, when she signed up as a volunteer caregiver. Kareem was almost 3 years old.

Nancy knew what the chimps were being raised for and she didn’t agree with it. She reached out to Dr. Jane Goodall for advice. Since the move to stop research on chimpanzees was still new, Dr. Goodall told Nancy that the chimps needed people like her, especially in that setting. So Nancy signed up and eventually became a paid caregiver at the lab.

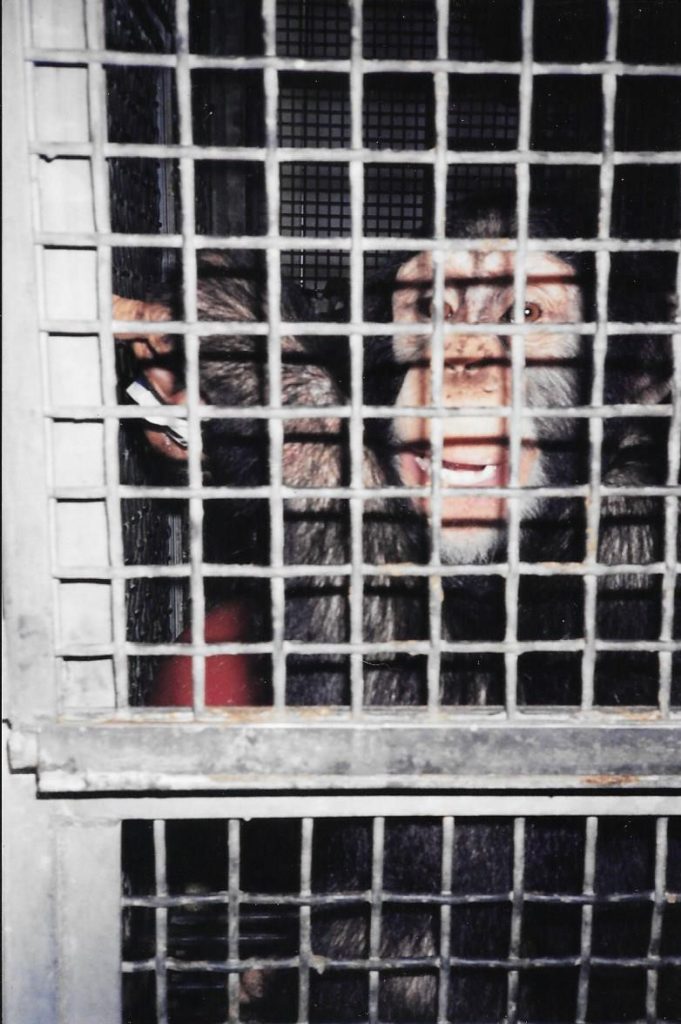

Nancy describes the nursery as a better place to be than the prison-like adult side of the compound, where the only contact with the chimps was through cage bars unless they were anesthetized. The nursery chimps had toys, blankets, playrooms, and hugs from chimp and human friends. Though the young chimps were caged overnight in small groups or pairs, they were taken to a playroom every day until they were about three years old. Nancy fondly recalls how Kareem would express interest in the baby chimps and would handle them gently. “He was the only chimp that would do that,” Nancy recalled. “Always bigger than the others, Kareem never used his size to bully or intimidate the other chimps. In fact, he would calm disputes and reassure the more anxious chimps.”

Kareem stays strong

Kareem hasn’t changed very much. At 220 pounds, he is the largest male chimpanzee now in permanent retirement at Project Chimps. Kareem is truly a gentle giant.

“I was smiling ear-to-ear for days when I found out that he made it [to Project Chimps],” Nancy shared. “And to hear that after spending all those years in four different labs hadn’t killed his gentle spirit. To hear that he’s still a gentle leader is just amazing,” she added.

As Nancy recalled Kareem’s years as a toddler chimp, her tone became somber.

“I remember the day Kareem didn’t want to go back in [to his cage]. If they didn’t go back in they would have to be darted. He was walking, bipedally, up and down the main hall of the nursery. We begged him to get in. We tried fruit and treats. That would be his last day in the playroom.”

After that day, he remained in a tiny cage in the nursery, never coming out to play again.

Kareem becomes a test subject

When Kareem was 5, it was time for him to graduate from the nursery to the “Junior Africa” area in LEMSIP. It was another milestone that made LEMSIP caregivers cringe. Moving to Junior Africa meant the chimps would only live in single or pair cages suspended from the ceiling of the lab with plastic wrap underneath to make it easy to clean. Giant Kareem was moved into a 5’x5’x6’ cage – allowing him no room to move more than a couple of steps in any direction. Kareem lived in a windowless room, unable to see the outside world. And that is where he would stay for the rest of his time at LEMSIP. All day, all night. Unless it was an experiment day.

At that point, Kareem became a subject of research at LEMSIP, undergoing routine participation in invasive studies that would involve him being hit with an anesthetic dart, which would “knock him down.” He would then be taken out of his cage, rolled into another room, where he would then be subjected to multiple biopsies so that the scientists could test his organs. This procedure would be repeated every few weeks or months for years on end.

Kareem gets the worst luck of the draw

In 1995, New York University announced its plans to close LEMSIP and transfer the chimpanzees to the notorious Coulston Foundation in New Mexico. Dr. Mahoney tried to find homes for as many of the chimps as possible. He arranged for dozens of chimps to move out of the lab before they could be transferred to other research facilities. But, in the end, he still had to send half of the LEMSIP chimps to Coulston. Someone had to decide which chimps would go.

According to the New England Anti-Vivisection Society (NEAVS), “To chimpanzees used in research, the Coulston Foundation was the worst luck of the draw.”

NEAVS reports, “In addition to the deaths [of research chimps documented at Coulston], numerous agencies found Coulston to be in violation of multiple federal regulations.” Virtually every federal agency and the national accrediting body for labs identified violations at Coulston of rules and regulations pertaining to animal welfare, housing conditions, and record-keeping practices.”

Dr. Mahoney was aware of the conditions the chimps would face at Coulston, so he reached out to Lisa to get her opinion on the mental and physical capabilities of the chimps she had raised. In particular, he wanted to know if she thought the trio of Regis, Digger, and Kareem, were strong enough to handle life at Coulston.

Kareem had something special

“Kareem, from the beginning, he had something. He had this inner well of stability, which was extraordinary. I’ve not come across another chimp like him. He would sit back but he wasn’t reserved. He was balanced in a way that was notable. We all saw that with him. With other chimps, he wasn’t super rowdy, super reserved. He was a chimp that you could always count on to do the right thing.”

“We knew Regis would never make it in research so he went to Fauna Foundation in Canada.” Digger … was sent to Ohio State University’s Chimpanzee Center, another facility with a better reputation than Coulston.

And Kareem? He was sent to Coulston because Lisa, Mahoney and the other caregivers agreed that he was most likely to survive the conditions there. No matter what was done to him there, they believed that he had the inner strength and psychological foundation to endure. It was of course a very hard choice, because Coulston already had a horrible reputation of neglect and abuse of its chimpanzee residents, but Kareem had the best chance of getting out alive and with his inner strength intact.

A new chapter begins at Coulston

On Oct 15, 1996, Kareem left New York and traveled to New Mexico to the horrors of the Coulston Foundation. It’s a day Lisa and Nancy will never forget.

Kareem’s role as a research subject would continue at Coulston, as we will explain in the third part of his story.

Lisa and Nancy cared for more than 50 young chimpanzees over the years. The last time they saw Kareem, he was a young, tan-faced chimp. Neither woman saw Kareem as an adult until twenty-two years later, when Project Chimps posted his picture on Facebook.

As soon as they saw the photo we shared after his arrival last month, they instantly knew it was the chimp they had loved and lost.

“It is difficult for me to express the impact of Kareem getting to sanctuary at this moment in time,” said Lisa, adding, “Kareem has been able to come through everything that research has thrown at him. It’s remarkable.”

We look forward to sharing the final chapters of Kareem’s journey on Dec 30th, which just so happens to be his 30th birthday.